Community Gateway

Back to Gateway

I am from the US, was born in Upstate NY, and spent about half of my childhood abroad in Europe, Africa, and Asia. My father was in the diplomatic corps, and where we were living in Nigeria at the time, the school there only went to 9th grade, and we needed to find a boarding school for me to finish off high school. We looked around Europe and visited a few schools, but St. Stephen’s was the one that stood out to me, and there was something about it that seemed unconventional and interesting. I was not wrong!

I was a boarder for three years, and this was the mid-eighties in Rome, so it was pretty freewheeling and a bit politically chaotic, but that was sort of in the background. Regarding life at St. Stephen's, there were only about 180 students and about fifty boarders in the school. It was like having fifty brothers and sisters with you; having breakfast, going to class, socializing in the afternoons, and going out on the weekends. It was such a revelation to arrive in Rome, be 4,000 miles away from my parents, and explore all of the charms that Rome had to offer both in and out of school. And we would go out at night, and there was always this race to get back into the school before the curfew, and you'd hop on somebody's motorino. I remember the gatherings in the parks underneath the stars, with bottles of wine, and it was just so much fun. Academically, what I always liked about St. Stephen's is that you had this anarchic, liberal, independent-minded student body, but it was fused with this rigorous academic discipline. I had inspiring teachers like Jack Ullman and Helen Pope. St. Stephen's is also where I started acting with Sandra Provost. It was exciting because she treated us like adults, like mature artists, even though we were kids. The material she chose for us was also very risque and not entirely appropriate for 15-year-olds, but she didn't care. And we loved that about her. She was very inspiring to me. I also remember Richard Trythall, who was wonderful; he was the soul of the school. Michael Stannus, who taught me English, was the first person who inspired me to write. I still remember him saying, "indeed, it reads very well," and those words stick with you when you're trying to make your way early on in those days.

I wanted to study theater. I took a year off from high school, and when I entered college, I went to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, near Chicago; they have a fantastic theater program there, and even even though I started in the theater program, I felt I needed some kind of validation, I don't know if I was any good at it or not and I felt like I needed to go work in theater, so I went to what's called a "Cattle Call" audition in the winter to find work for the following summer. All the theaters come to one place, and hundreds of actors audition. I auditioned in February of my freshman year, and I ended up getting fifteen months of work. I was offered two contracts, one for the summer and one for the following year, as an actor. At the time, I was nineteen, but I looked like I was fourteen, so the parts I got were for teenagers; they were happy to have an adult who could play a teenager. I ended up getting work in Ohio, in Arkansas, and that's how I got an Equity card. When I returned to college, I was more focused and had a great acting teacher. I also started making forays into directing theater and enjoyed it. My acting teacher at the time made us show up an hour before class and do what we called "the workout," and part of the workout was called the "corporal mime," which was an obscure physical theater technique invented by Étienne Decroux in 1920s France. It was rigorous, like a mix of ballet and gymnastics, and I realized that I was physically uncoordinated and felt like I needed more of it. After college, I didn't relish the prospect of hitting the streets as an actor in Chicago, so I jumped at an opportunity to go to France.

I ended up in Paris, and through busking as a musician, I met this entire community of street musicians and more established musicians. I fell in with a group of Irish musicians. We played the Irish pub circuit in Paris for a couple of years, and then one day, I saw Marcel Marceau perform in Paris, and I remembered that I loved theater. I had been away from theater for a couple of years, and he had a school. So I thought that would be cool; I auditioned for the school and got in. I really liked him. He is kind of a legendary character, but he wasn't a fantastic teacher. There was another fantastic corporal mime teacher there; she taught this obscure technique and had a school in the suburbs of Paris. I started moonlighting at her school after Marcel Marceau's school. I loved it. When the school decided to move to London, I became a member of their company, and I consider studying mime my film school because it taught me how to think visually. I learned how to imagine a body in space and think through a story visually. It also taught me something about the editing process, which, as Kubrick said, is probably the most unique part of filmmaking, and it's what filmmaking owns more than acting, more than cinematography, more than sound. I started making little films with my friends, and it was around this time that digital video was just arriving, in the late nineties. It started to become possible to edit digitally on a computer so you could conceivably set up your own home studio, which I began to do while I was living in London, the heart of the British theater and cinema scene. I found a job working as an assistant for a feature film producer who was doing five to ten-million-dollar big, full movies, and that was incredibly valuable for me because although it wasn't at all artistic, I learned the whole backroom side of filmmaking and how you put a film together. And then, I began making my way, making a living shooting corporate videos and short films, and eventually, that led me along a more linear path to what I'm doing now, which is making feature films.

There are a couple of things. One of the things I've learned is you have to take a long view, especially for arts, because it's not just about playing your cards right and networking and meeting the people, but it's also just a long kind of slow drip process which is this interface of your soul and your experience with your talent and your technique, and all of those things take time to grow. And so it's useful to take a long, ten or twenty-year view of things. You may wonder, "How will I fill all that time?" But you do, and you'll have love affairs, you'll meet people, you'll have jobs, you'll be fired from jobs, have friendships, travel places, and you'll have heartbreak. All this stuff will come at you no matter what as a human being. But that's all grist for the mill.

I was talking to Helen Pope the other day, and I remembered how when I was nineteen, and even in my early twenties, I was obsessed with Ingmar Bergman, the film director. I watched all his films, studied his life, how he made each film, how he met the actors and knew everything about him. And then, when I hit thirty-one or thirty-two years old, I OD'ed on Bergman; I suddenly didn't want anything to do with this guy. I think part of it was me telling myself, "I'm never going to make this work. Come on; I'll never make a film like that." And the funny thing is when I made this most recent film, Under Spanish Skies, it's a very Bergmanesque film, the way I set it up with characters who have known each other for a long time. I had no intention of doing this, but I ended up making a Bergman film in my own way, and it's interesting how there is this whole circular process of how you absorb something; you have an apprenticeship to the masters, whether they're people you know or those you study from a distance and then you have to let go of them at one point. Ultimately, life comes back around, and where there was once the mystery of "how did they come up with that idea,” that just comes out of you because of your life; it comes to you years later when you're writing without you being conscious of it. So, it's essential to take a long view. Another thing is: don't be too worshipful. This is the same advice you give to people who want to become parents. You're never going to be ready; you just have to have the baby and go through all the craziness. It's the same thing with art. Don't put it off if you have this inclination to do this thing, whatever the thing is, if you're a musician, a painter, or a writer, just start. You have to jump off the deep end and do the hard bit. Instead of making one small painting, do a painting that takes up a whole wall, draft a feature film, write a symphony and fail. You probably will fail.

And that's important. Get comfortable with failure. It’s okay because then you know you're in the arena, you have been bloodied, the bull has taken his first chunk out of your body, and you know you're going to have to go back and face him again. A lot of people are just afraid. Many young artists think, "well, what if I go to graduate school and study a bit more?" Or, "I need to work a little longer with this master because he's really accomplished." You have to cut the cord and jump, especially in the arts. This isn't the case with being a doctor; of course, a doctor has to attend medical school, but there's no reason to stay in school for too long as an artist. You're just putting off the inevitable.

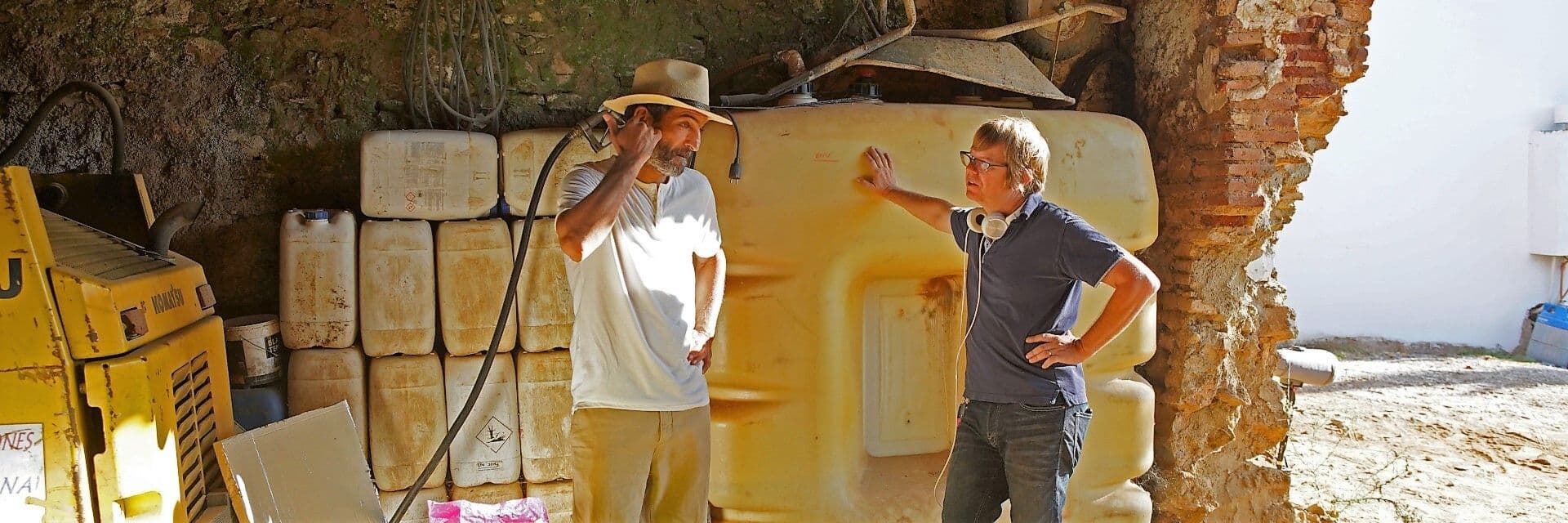

This film started because, while I had made a feature-length documentary before, I'd never made a feature-length narrative film. I was turning 49 in the fall of 2018. My wife, who is also a very accomplished artist, a dancer, and a filmmaker herself, knew that I had this thing that I'd wanted to do for a long time, which is make a narrative film, and she said, "this is your 49th birthday, why don't you make a film for your 50th birthday? That gives you one year to get this done." And it was a.good push. When you have children and are married to somebody making a film, it's a huge sacrifice because it will take up their entire life and your life. I recognized that this was truly a gift. She gave me the green light and said, "I know it's going to be tough for all of us, but you've gotta go through it with it." So I had that first impulse but didn't have a story then. I also didn't have money to make the film, nor did I have a place to film. So, I started searching around. I did have a set of parameters that I knew would work well for a feature film. The first was that I wanted to shoot in one location, and I wanted it to be set in a limited period of time, either twenty-four or forty-eight hours. I also wanted the characters in the film to have known each other for a long time because, in this kind of film, you excavate the past. So, you use emotional pyrotechnics instead of expensive real life ones like car chases and explosions. There's also the practical advantage of taking the whole crew with you and shooting the film in one place. And this goes back to Aristotle, who discussed the unity of time, place, and action. It turns out he was also giving us a recipe for low-budget filmmaking.

There is a certain subset of films that have followed this formula well, films that I love like Jean Renoir's "Rules of the Game," "The Big Chill," or "Festen," by Thomas Vinterberg. So, I had a structure, but I still needed a theme. I ended up traveling to Venice to discuss a business idea with a St. Stephen's contact named Frank O’Halloran, who was, at one time, the Head of Boarding at St. Stephen's, and we've been lifelong friends ever since meeting each other. He's a little older than me, but over time, that difference seems to have shrunk between us. We were sitting in Venice, on a terrace overlooking the Giudecca Canal. He starts telling me a story of an elderly couple he used to know who had a very interesting arrangement. They had a suicide pact. They had agreed that if one of them were to die before the other, the other person would take their own life, not wanting to live without them. And they went through with it. They were quite wealthy; they had an apartment in Marrakesh, Morocco, and in the apartment, they kept poison with the plan being that one of them would go to that apartment, drink the poison, and end their life. Importantly, they didn't have kids, nor did they have a close family. They really only had each other. The husband was always very athletic, running marathons at sixty, and the wife had a lot of health problems but, ironically, he developed a very fast-moving cancer, and from diagnosis to death, it was only three or four weeks.

He was gone, leaving her alone. She spends six months traveling the world, getting rid of their property, and giving their money away to charity; she comes back to Venice, says goodbye to everyone, and, of course, everyone already knows about the arrangement, and they try to talk her out of it. She tells them, "no, I'm going to go through with it." She flies to Marrakesh and ends her life. I was back in Berlin a couple of weeks later, riding my bike, and I realized, this is it; I can use this. So I took this story and put it together with the format I had planned. I imagined the main character who is living alone, she has just lost her husband, and she invites her two best friends, who have known her since high school, to visit. A lot of shared history between the four of them comes out over the course of the movie. I based a lot of things on my St. Stephen's friends, and I was thinking about St. Stephen's as I wrote the film. I think those years, between fourteen and eighteen, disproportionately influence your life, at least they did for me. St. Stephen's certainly did. So, for these characters in their late forties and early fifties, there's a reckoning that happens.

The script basically wrote itself. I wrote it very quickly, and I was able to raise money off of that script. I wrote for some actors I knew and then for others I met. I went to Venice in January, wrote the script in March or April, raised the money in May and June, did pre-production in July, and filmed in August. It was a three-week shoot. For a feature film, that almost never happens; a feature usually takes three to five years to progress from no script to a completed film. There was almost something supernatural about it. So we did it. I shot the film before my fiftieth birthday. It took me a good two and a half years to edit it. Part of that was that the whole film industry just shut down. We shot in August of 2019, and then the whole world shut down in March because of the pandemic. It was probably a good thing for the film because it gave me a longer gestation period to go through the editing process. And the thing I always say about movies is that you really write them three times. You write them when you write them, write them again when you shoot, and write them a third time when you edit, and each time everything transforms a little bit. So that was a good process for me.

It definitely wasn't intentional, but I think there is a subconscious process we can't avoid as third-culture kids. We grew up with a sort of ease of transition from one culture to another or from one language to another. I wrote it in English, it's set in Spain, there's only one Spanish character in it and the guy who plays the Spanish character is actually Egyptian! I guess I was reaping my friendships with other professional film people that I have known for years and who live in the UK, Spain, the US, Germany, and France - and then we had the luck to be put in touch with Amr Waked, who is Egyptian but lives in Barcelona - who played Andrés and with Nahéma Ricci, who plays Alix who is of French/Tunisian descent but lives in Quebec. I wrote for them and Tullan, Swedish/Italian, Philippe, Dutch/British, and Tara, an American living in Berlin. I really didn’t think of them from the standpoint of their nationality; I just admired each of them as an actor and shaped the script and the character around them.

I consider this film my greatest achievement in terms of my work. Of course, I also hope that the next one will become my new greatest achievement! In the bigger picture, my greatest achievement was convincing my wife, Megumi Eda, to marry me, which was not an easy thing to do.

Definitely not. I was always in the artistic realm, but I was pretty dead set on being an actor when I left St. Stephen's, and then I went into music for a while and thought maybe I'd just stay on that path. I meandered; there were so many dead-end paths and detours. For me, it's been anything but linear. I didn't even know I wanted to direct films, although I have a clear memory of one moment from my senior year in college when I was at a party, and the girl I was talking to asked me, "what do you want to do?" Without thinking, I blurted out, "I want to direct films." At the time, I didn't know where that came from, and I didn't do anything involved with making movies for a good ten years after that, but I had this vague notion that that's what I wanted to do. I did a lot of other things in the meantime, including having a family and all the joys and responsibilities that engenders. So, I followed a twisting, meandering, anything but a straight path.

If your experience is anything like mine, the friendships you will make these years, the impressions, and the things you learn in school and out will probably influence your life more profoundly than any that come after. If you have an inkling that there is something that you are good at and love doing, even if it is a very secret little notion right now - you have so much time to nurture that tiny impulse into something great and magnificent. Think in terms of 5 years or 10, or 20 years. Those spans seem infinite when you are 16, but to do anything well, you must get used to long-term thinking. Don't worry about not getting an audition in your first year of hitting the streets in New York or even in your first two years. If you haven't done it in five years, you can start to question things after going full out, but remember to think in terms of those time spans. Don't give up before then. It's also useful to think in terms of a body of work. Don't have a passion project that has to become your great masterpiece because, inevitably, your first idea isn't going to work; it won't be as good as an idea you have three or four projects down the road. So just get the work done and start building a body of work. Let people judge you on that, not on a specific project.