I'm from the U.S. My dad was a career foreign service officer from Nebraska who specialized in the Middle East and my mom is from California. I had transitioned to the U.S. in middle school, moving from the Middle East to Arlington, Virginia and the culture shock was tough. When we got the news my dad would be posted overseas again – this time in Damascus – we knew it would mean boarding school for me. I remember telling my parents I didn’t want to go to school in the U.S. so the family services rep from the State Department recommended St. Stephen's, which we thought it would be a good fit because of its strong theater program.

Here’s a fun origin story: I was at Dulles Airport waiting for the flight to Rome, weeping inconsolably, terrified because I didn't know what I was getting into. I was fifteen, what would I know? The girl sitting next to me at the airport (who got me to calm down) turned out to be Marina Rheault [now Marina Post], a student at St. Stephen's who wound up being my roommate senior year and we’re still very dear friends. So there was almost a feeling of destiny to my attending St. Stephen's from the beginning.

There were so many! They fall into two categories: this abiding sense of the wonderful things that went on all the time and some specific incidents.

First of all, the boarding experience was life-changing and made me the person I am. When you're a teenager, you forge such strong relationships because your emotions are so powerful, everything is new and constantly changing. I had two roommates in two different years, Kathy Fisher and Marina Rheault and I remember one night being in the room with them, talking about anything and everything, being domestic, making the space beautiful, and having this profound feeling of belonging, of rightness with the world, and closeness to other human beings. That warm feeling is something I always have when I think about St. Stephen's.

So that's one general thing, a big one. Another was the incredibly high quality of education and the way the teachers, specifically Jack Ullman and Peter Rockwell, made history come alive. We're in Italy, the most extraordinary historical playground in the world, and they made full, magnificent use of it. I remember the first paper I wrote for Jack Ullman in my Medieval-Renaissance class sophomore year. I have no recollection what I actually wrote about, but what I got back was astonishing and revealing – Mr. Ullman had read my paper with such care and interest, with such long, thought-provoking comments in the margins! Two things came to my mind, the first was, "Oh my goodness, this stuff is interesting," and the other was, "Oh my God, I, as a person and as a student, have thoughts and ideas worthy of this level of commentary." That started my lifelong passion for history and informs my playwriting all these years later.

I remember the time the boys moved Steve Altschul’s Fiat '500 to the chapel porch one night [laughs] and I remember being in my dorm room one day around noon and hearing this tap on the window...I looked out there’s Peter Semler! He had climbed out of his window, down a pipe on the exterior of the building, and, having realized he couldn't climb all the way down to the ground, he knocked on my window to get back inside. There was also a certain amount of sneaking out after hours that went on, nocturnal trips to the Protestant Cemetery, Orange Park, the Vittorio Emmanuele monument – [laughs] is it OK to tell you this?

Reflecting on my time at St. Stephen's, it was a time of adventure, belonging, and genuine intellectual stimulation. I went to a great college, but those history, English, and art history classes at St. Stephen's awakened me intellectually as nothing else has since, lighting a spark that has led to lifelong curiosity.

I lived in Damascus with my parents for six months, then went to Wesleyan University in Connecticut. After college I moved to New York and then to Paris to study art restoration where I got strangely homesick for America. Studying art restoration should have been glamorous and fabulous but I had this feeling it was not really what I should be doing with my life and I wanted to know what it was like to be an American and live in a country where I could vote – that was important to me. My family was overseas and I didn't want to return to New York but my boyfriend from college was working at the Berkshire Eagle, a local newspaper, so I decided to join him. Then there was a stint in San Francisco, and I’m in New York and DC all the time but I’ve basically been here in the Berkshires all these years. What's remarkable about this moment in my life is that I've found a new path with my playwriting, a new beginning for me in my fifties and I’ve been getting traction with it. I feel like a phoenix.

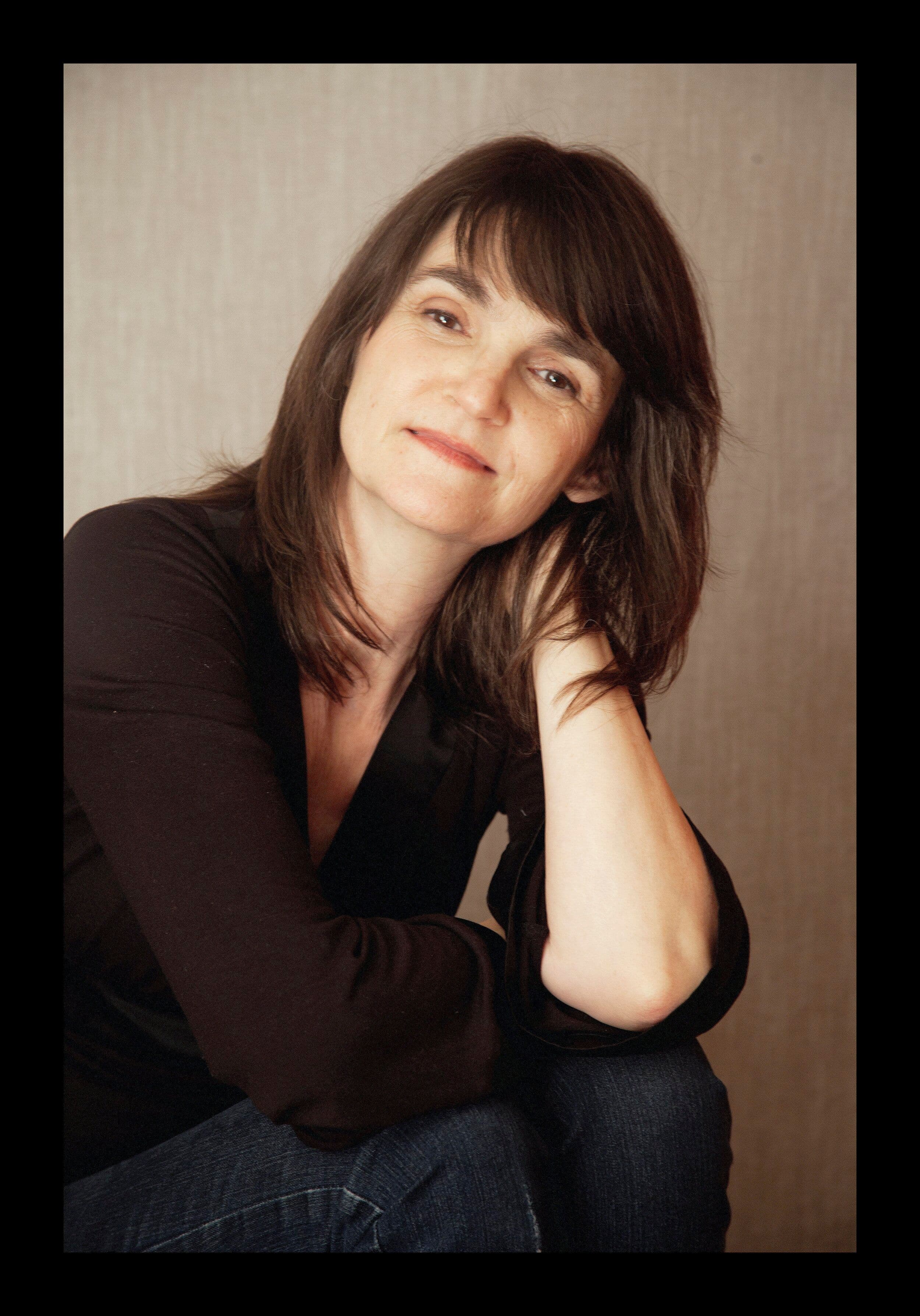

Yes, I was definitely a theater kid and at St. Stephen's I was lucky enough to have had a lot of great roles. I always saw myself as an actor.

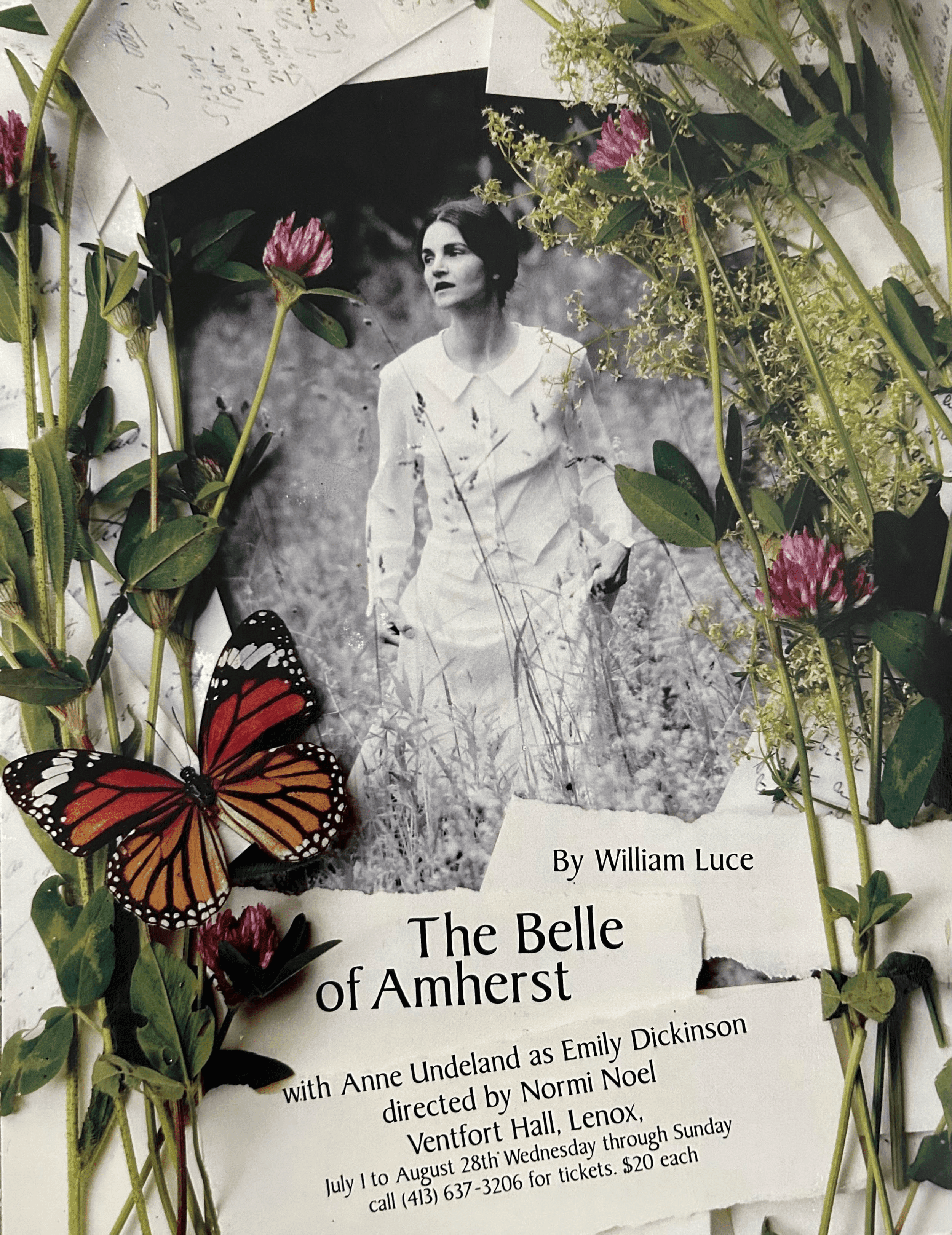

After I had my son, I started to specialize in one-woman shows, largely because as a single mom, it dovetailed into my parenting schedule. When my son reached an age where he didn't need me as much anymore, I planned to go back to doing more plays with other actors. However, I was around 50 and soon realized there just weren't that many significant roles for women my age. We're usually a side character, someone's mother or some authoritative figure like a district attorney or a judge, rarely the person driving the action or having the romantic or sexual relationship. I wondered, "Why can't we be primary characters, and why can't we have sex be a part of our stories in a way that's not sensationalized or mocked or not spoken about at all?" So, I picked up my pen and thought, "Why don't I just write one of these stories?"

My initial idea was to write a one-woman show based on an historical figure so I went looking for female figures with universal George Washington-level name recognition but soon saw there really aren't any! There's Queen Victoria, Mary Todd Lincoln, maybe Susan B. Anthony, and, can you name any others? There just aren’t that many. When you start thinking about it, you see that women are simply not part of the story, especially women over forty-five. So, if I was looking for name recognition – and I was – I would have to find a woman associated with a famous man.

That’s when I came across Jennie Jerome, Winston Churchill's extraordinary American mother. It's fascinating to think that Churchill, “the greatest Briton,” was actually half American – I would argue he got much of his tenacity, determination, and chutzpah from his Brooklyn-born mother. She was so interesting; one of the first "dollar princesses" (wealthy American heiresses who married into impoverished European, mainly British, aristocracy), she freely had lovers and was a brilliant tactician and political maneuverer. She engineered her husband, Lord Randolph “Randy” Churchill’s meteoric rise in British politics (Winston’s father had quite a career before he was felled by what was probably syphilis). Despite her brilliance, however, whenever you see a movie or read a history where Jennie Jerome is mentioned, there's always this implication that she was loose morally, a bit of a harlot. Yes, she freely and unapologetically had lovers, but what gets me is that if her behavior had been done by a man, he'd be a rake, a sort of rogue, and people usually find that sexy and admirable. When a woman does the same thing, she's a whore. Shame is a method of control. My play’s called Lady Randy and it shines a light on that double standard. I initially thought of it as a one-woman show but a friend suggested turning it into a two-hander, so there's one actor playing Jennie, and then a second actor playing all of the different characters in her life. It’s a memory play with her on her deathbed, coming to terms with her life in a series of flashbacks and vignettes. It was produced by WAM Theater and had a terrific run at Shakespeare and Company here in the Berkshires.

My next play, Wharton Between the Sheets, was performed at Great Barrington Public Theater and Boston's Gloucester Stage and we just did a reading in New York. I'm now in the middle of a commission to write a new play about Mozart's wife, so stay tuned.

Over these past few years, I’ve seen a hunger for stories of women over 45. It’s also good business. A recent study found that 69% of Broadway tickets are purchased by women over 45, so you’d think we’d want to see some of our own stories too! And there is a change taking place--which I am thrilled to be a part of – older women are seen as more relevant and less invisible. Being part of this change is what drives a lot of my work.

I'm always interested in a woman who seems to be misunderstood or maligned by historians. That always makes my antenna go up. Constanze Mozart, for example, has been referred to as not very bright, loose, and, worst of all, a bad housekeeper. I find myself asking, “hmm, really?”

The antenna that went up for Edith Wharton was a little different. Even though she’s one of my favorite authors, I always thought of her as this forbidding, austere character, a great mind but someone who would never be a good subject for a play.

Then I read an article about her having had a midlife affair and I remember thinking, "well, that's interesting." A few years later, I came across some erotica she wrote called "The Palmato Fragment," which surprised me. And finally, during the pandemic, I read the letters she wrote her lover, Morton Fullerton, and I was bowled over.

What astonished me (beside the fact that her words are far more beautiful than anything I could ever have written) was the realization that I could have written those letters. Her story has a universality because pretty much all of us have had the experience of being madly, passionately in love; it's horrible, it’s glorious, it's an experience I wouldn't wish on my worst enemy, and I hope to God it happens to everybody. The fact that this happened to Edith Wharton, this forbidding character, was so interesting to me.

So I started digging further. At the age of 45 or 46, Edith Wharton was in a loveless marriage, a sexless marriage, but to the outside world, she was a huge success. Her novel, The House of Mirth had sold over 150,000 copies, everybody wanted to meet her, she was always the smartest person in the room…and then she’s entirely levelled by love. Her letters are so touching and funny. In one she’s saying, “I think of nothing but you, I love you, I want to give you all my treasure," in the next she writes, "if you don't write me back, I shall never write you again!" And then a day later she begs, "Please, please, please write me back, why won’t you write back?" I wanted to explore her desperation, bewilderment, vulnerability, all of it.

For the Edith Wharton of my play, her sexual awakening was an earthquake and a rebirth. Morton Fullerton was a person who couldn’t be pinned down but everyone was in love with him, including Edith’s dear friend, Henry James (deeply closeted but still besotted). Unfortunately, Morton was also a man who couldn't be faithful to anybody, it just wasn't in his nature, which caused enormous pain for Edith. Ultimately, the relationship ended because he started to ignore her, began to treat her as if she didn't have value, and at a certain point, she woke up from her love madness and said, "You can't treat me this way."

I think Edith Wharton’s greatest masterpieces were born out of the affair – the experience woke her up artistically in so many ways. Morton Fullerton may have broken her heart but in doing so, he did us all an enormous favor.

Writing that play was an opportunity to look at the power of sex in our lives. It’s a worthy subject. While there are no actual sex scenes in any of my plays, the suggestion is potent and enlivening. As a playwright, I’m always looking for character, and sex is one of those things that is both utterly revealing and completely mysterious – it can make people behave in strange and surprising ways.

I do. I participate in the London Writer's Salon, an international group that meets daily on Zoom for an hour in which all we do is write. There's something about being with a group of people all in our Zoom boxes, all doing the same thing, coupled with the discipline of writing every morning that keeps things flowing. Creativity is a muscle. Inspiration needs to know it can rely on you. There's this myth that creative inspiration comes in and overwhelms you, you write your masterpiece, and then you're done, but it's more pedestrian than that. You have to work at it. You have to create a reliable setting, and then inspiration, or the muse, or whatever you want to call it, can come. If the muse knows you'll be writing every morning then she’ll show up – maybe not every morning, but some mornings, she will. I live for those mornings.

I'm also part of a couple of different playwriting groups, very helpful as a way to get out of my echo chamber. Writing can be lonely. What’s more, I need to hear the words spoken aloud and we do that in these groups; they also create mini-deadlines, which is helpful.

The fact that my plays are works of historical fiction comes out of my experiences at St. Stephen's. In the classrooms of Jack Ullman, Peter Rockwell, and Dikla Peebles especially, I became good at feeling what it was like to move through a different world, to walk the streets in another period in history. These experiences gave me a vivid, visceral picture. I find that as a playwright, I can put myself into the world of my subject, I can picture what their houses looked like, what the food smelled like, the sound of the church bells, what the sheets felt like, what the music sounded like, and that's how the play develops.

I love a love story. And most worthwhile human experiences are, on some level, love stories. So, find what you love to do and the people you love to be with.

When you’re with someone who’s doing what they should be doing with their life, there's almost this clicking noise. You can feel it. I know I felt it when I was in Jack Ullman's classroom. The man was a brilliant historian and teacher of history; you felt his passion and it was so inspiring. Sometimes it takes a while to find that click, that thing you love and that's okay. Try things, have adventures, no idea is stupid. Be sincere. Irony is great, but cynicism doesn’t get you anywhere. Be aware of the voices in your head that tell you you shouldn't do something because it's impractical. Don't stop til you've found it. Again, it may take a while. Life is a love story.

Community Gateway

Back to Gateway