Community Gateway

Back to Gateway

CEO & CO-FOUNDER AKILI NETWORK

I was born in Chicago and left at the age of six months to move to Athens, Greece. I am the son of someone who worked for Caltex Oil and we moved around a lot. When I was in ninth grade, we were living in Madrid. I had just moved from Beirut and my grades were too good, according to my mother, for the amount of work I was doing, so she looked for a more challenging school. So, in 10th grade, I was sent to St. Stephen's as a boarding student, spent three years there and graduated from St. Stephen's.

I made “forever” friendships. St. Stephen's is where I met my wife. We're still married. She's here working with me in Africa. The School was so important in terms of lifelong friendships. When I think about where really good friends come from, it's from high school, not college. The first business I set up was with a classmate and then we were joined by another classmate.

The other important thing was the quality of the education. The School took advantage of its location in Rome. I remember fondly reading Ovid's "The Art of Loving" outside in the garden of the villa (this was when St. Stephen's was in Parioli). If you're going to make Latin enjoyable, that was an excellent way to do it

I had some phenomenal teachers, one of whom I know has been back teaching at St. Stephens, Ed Steinberg. When, as a senior in high school, someone gets you to read Freud, study sociology and learn about socialism, it opens up the world of adults; you're still a kid, but you see that there's this other world out there. I went to a good college, Swarthmore, but I didn't feel there was anything qualitatively different that I hadn't already experienced at St. Stephen's.

I remember just being able to enjoy Rome, the food, the rowing program at St. Stephen's, where we would row on the Tiber. I also remember when a teacher arranged for us to visit the Vatican Archives and, years later, when I saw the movie set in the Vatican Archives with Tom Hanks and there was all this security, it made me think back to how special it was that when we were able, as students, to get a tour of the Archives. I still remember the tour guide pulling out a flat file that contained this big manuscript with a gold seal on it: "this is from Emperor Maximillian to Pius IX" and the translated the letter, which was basically Maximillian saying, "Pope, send money and troops!" And this is before he's assassinated. Seeing a letter like that is priceless and memorable.

When I went to Swarthmore, I intended to major in economics. I dreamed of working on Wall Street, making a lot of money, buying an island, and inviting all my friends. That was a relatively immature and perhaps unrealistic dream at the time. I was majoring in economics and in my first semester, senior year, I decided to take a course in cinema theory. Swarthmore is typical of many liberal arts colleges in that they don't have a film production path; you learn the history of cinema and the semiotics of cinema, you watch movies and talk about them. I decided to make a student film. It was not a great film, but it got me interested in film and I ended up switching my career path. I changed into a minor in English instead of political science and, after college, I went to New York City and started looking for a job in the film. I remember that I was very appreciative that my parents didn't have some preset idea of "we want you to do this." My father was like, "whoa, okay, let me see who I can introduce you to who might be helpful."

So, I think back to that time and I remember that many of my classmates became doctors, they became lawyers, and then the people who didn't know what they wanted to do became teachers. I was in a tiny subset that did something different. Three months ago, I reconnected with a classmate from Swarthmore from Kenya. He was an economics major; I was an economics major and we shared a lot of the same teachers. We hadn't seen each other in 49 years, but he continued on the path of economics and is currently the Chairman of the Central Bank of Kenya. So, he did just fine pursuing economics and here I am running a children's TV network in Kenya.

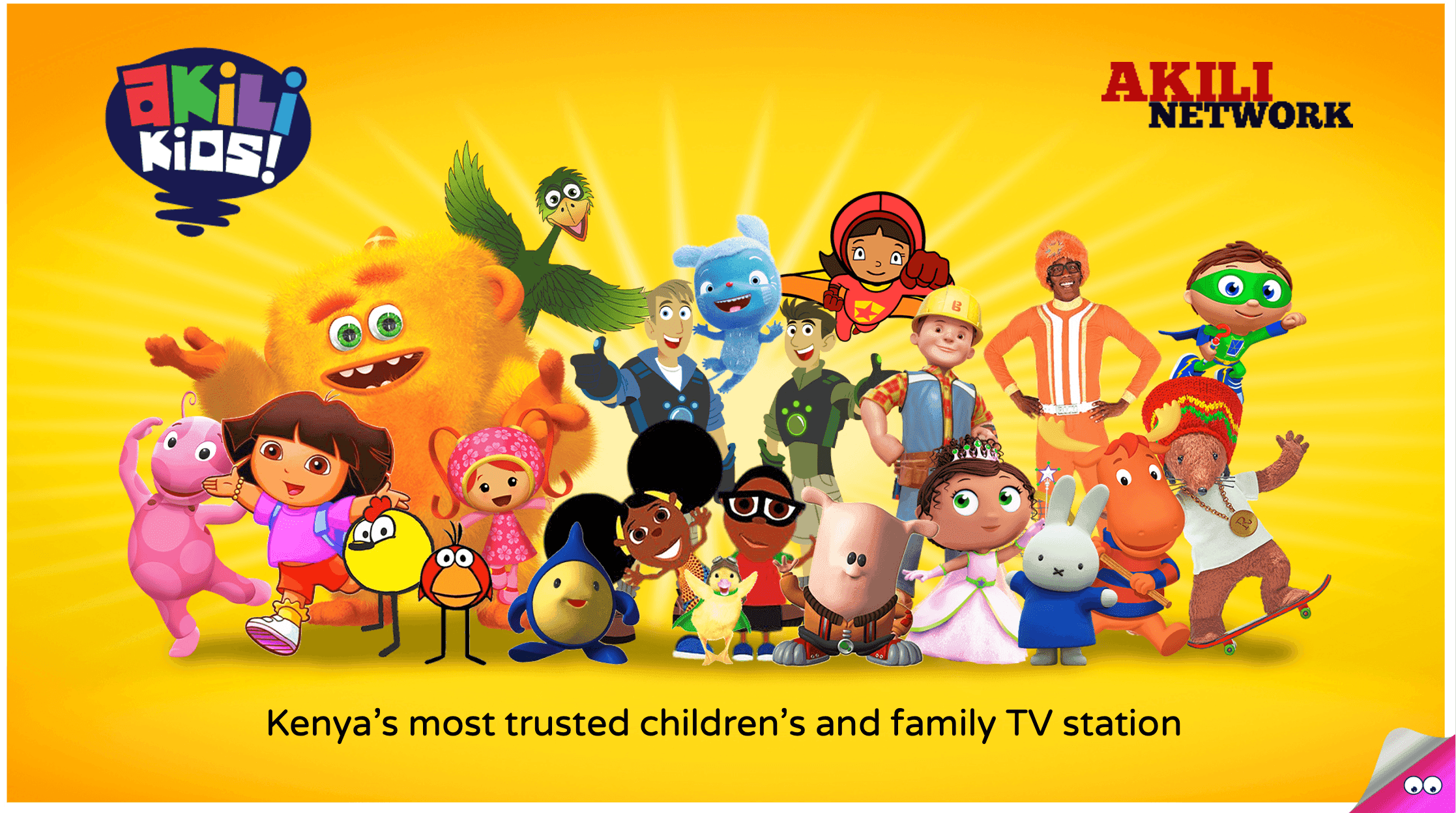

Yes, so Akili Network is the company that launched Akili Kids! which is a free-to-air children's TV channel in Kenya. Think of it as PBS Kids type of content, but a Nickelodeon business model. We are commercial.

There’s a range, with TV being a combination of education and entertainment, and digital can often be more educational. For example, at Scholastic Inc. I spent time doing digital interactive content, particularly reading remediation software that's really trying to teach and instruct and where you can individualize [the product]. Whereas TV is a medium that helps with creating mental models; it is very persuasive, it's motivational, it can have a deep impact, but it's not going to be the best to teach calculus. Although, with something like Khan academy, where you have learning objects and can be very specific in terms of learning about one thing, then linear media can be just fine. But we're doing broadcast. I sort of stumbled into it in terms of a career that took a lot of twists and turns. One thing led to another.

But in terms of Kenya and how that came to be; I had been working at Scholastic in the education group and I hired, in 2002, a fellow named Jesse Soleil to work in my group as a producer, and around that time he met a woman from Kenya who he then married. Fast forward to 2010; I've left Scholastic, Jesse leaves Scholastic, and we start working producing transmedia programs for kids. Because Jesse had been spending a lot of time in Kenya, he ended up being contacted by someone who was working for the government who asked us to think about how to expand the media economy in Kenya. We did a little bit of pro bono work that led to a trip in 2012 to Kenya. We thought that it would be great to do educational consumer products, things like coloring books, which develop fine motor skills in children, and depending on what the content is, a way to learn things like the nouns for flora and fauna. But, we thought, if we are going to do educational consumer products, it would be great to have some airtime on a TV channel. We asked our contact, Michael Onyango, “which of the broadcasters should we speak to about giving us an hour or two of time to broadcast some children's content that would promote these educational consumer products.” Michael told us, "No one." He said, "Well, if you meet with them, they're going to ask you, do you have a sponsor? An underwriter? Or an advertiser? and then they're going to tell you how much they're going to charge you to put your content on the air and then tell you that they're not going to do a revenue share." We said, "Michael, you're right. We don't want to meet with any of them." [laughs] but he told us Kenya was in the middle of a transition from analog to digital broadcasting which increased the bandwidth for more TV channels. Michael said, "I can set up a meeting with the Communication Authority of Kenya," which is the Kenyan equivalent of the FCC in the US, "and you could apply for a license to have your own channel". We went to the meeting and they told us they had closed the application process but, because we wanted to do a kid's channel and nobody had applied for one, they would open it up for us. It took us a year to develop the business plan to get the license. So, it was through my now Co-Founder and partner that we ended up launching a TV channel in Kenya.

Going back to my early days of being interested in economics, the only part of economics that I was truly fascinated with was development economics and wondering, "how does an economy start? How do you grow an economy?" And here we are, building media jobs in Kenya. We have 25 full-time employees. All this started because of a conversation that happened at the end of 2011, a meeting in 2012, and then the journey was a long one of finding funding and raising the money. We didn't give up. At least in my career, there are plenty of projects you get very excited about at the beginning; there's this wild enthusiasm. Then maybe three or four months later, you discover someone else has already done the idea, it's suddenly not so interesting and you move on. With this project, every year that went by, it became more interesting, not less. We finally got our funding from an impact investor interested in doing something positive for the children of Kenya and thought that instead of building another school and impacting 300 kids, why not invest in a TV network that could impact five million kids through broadcasting content. There are 20 million children under the age of 14 in Kenya. We're reaching five million kids every week.

There are a couple of things. One of our most recent investors in Akili is an organization called Acumen, who are impact investors. In doing their due diligence they did both business due diligence, to validate the business model, and impact due diligence: are we having an impact? They commissioned a third party to interview parents of children that were watching Akili Kids! and, in the report they produced, the impact was well beyond anything we could have imagined. 95% of the parents surveyed said, "Our children's academic performance improved significantly", and five percent said it improved. So, a hundred percent said it was having a positive impact. On a more granular level, 45% said “it improved my child's English.” Others said it improved their child’s math. Others said, “My child is better behaved” because of some of our programs focus on social and emotional skills.

A lot of studies have been done on programs that have an educational impact. Sesame Street has done a lot of that and can certainly establish how television can accelerate school readiness. You can teach all kinds of things. We have a show that is teaching ABCs, but there are other more subtle things, where we are modeling behavior. TV (video) is a very powerful medium. Many of our shows have strong female characters, and if you see enough of those shows, it's going to change your perception of what a girl or woman can or can't do. We have a show from public broadcasting in the U.S. called “SciGirls” and it's geared at getting 8-to-12-year-old girls interested in science. As a girl that can be inspirational.

There are different ways in which the television and linear video content can teach. We recognize that a show for a two-to-five-year-old is different than a show for a six-to-eight or nine-to-twelve-year-old. We think about who's going to be at home at what time and we do programming blocks for those age groups. There’s a show that I developed called Peep in the Big Wide World, that was produced by WGBH in Boston, which is a preschool science show. It's story-based and fun, with each episode’s story about a science concept that's appropriate for a three-to-five-year-old. As you go up in age, it becomes either showing kids something about the world that they might not otherwise see or it can be motivational, it can be social, it can teach emotional skills, it can be around promoting imagination. It's what you would call “supplemental education,” it's not core curriculum. It's not what's being taught in the classroom, but fits into the whole child approach to education.

In Kenya, TV was the best solution at this time to reach the maximum number of people because data is expensive here and not everybody has a smartphone. Certainly, very few kids have smartphones. We have some of our content on YouTube, with over 3 million views per month, but most of that happening outside of Kenya. So, to get back to your question, short content is something that can be viable for education. TV is a funny format because we must program 24/7, so you have content that tends to be a little bit longer. Still, one of the things we're looking at is licensing content that is on YouTube, that's short and good, and that we can package together as a half-hour. I don't think duration is an issue but it's worth asking, "What are you trying to teach? What are you trying to communicate?" Think of thirty-second advertisements. They figured out how to cram a lot into thirty seconds to persuade you to do something and I could use the same thirty seconds to convince you not to text and drive or whatever change of behavior you want to achieve.

We always knew from our very earliest business plan that geographic expansion would be a growth opportunity. Regional expansion is becoming more attractive to us and we want to expand the network into Sub-Saharan Africa. We've learned a lot in Kenya and we can see that the product market gap that existed in Kenya exists everywhere in Sub-Saharan Africa. There is no good, free children's educational content and TV is the cheapest way to reach the largest audience. We started in Kenya as free. We're still free but we also have been picked up in Kenya by all the three satellite providers that are offering subscription models. We are one of their free-to-air channels they carry and they have all asked us, "When can we take you to the other five or ten countries that we're currently serving?" They see that what we put together has value and we would want to replicate that as we expand.

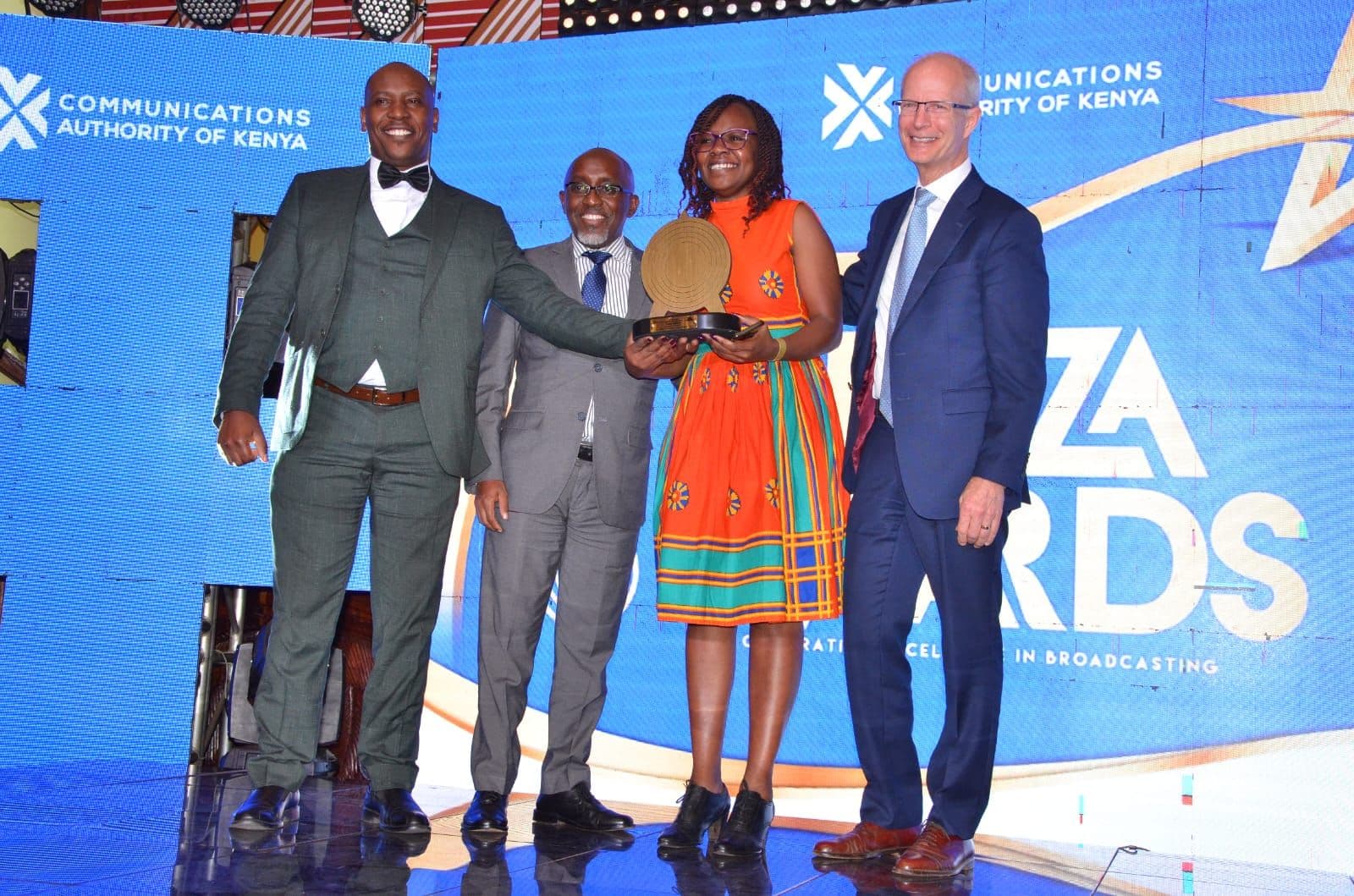

So, where do we get our content? To begin with, we licensed 95% of it and the criteria we used was, "Is there a learning outcome and is it entertaining?" And then, we used our Kenyan programming team, asking them, "Do you think it will work here?" That was how we curated the content to program the network. When we launched, the other thing that we did was, aside from calling it "Akili Kids!" which means "smart kids" in Swahili, we did station IDs that feel Kenyan, so the channel's branding is perceived as Kenyan. Recently we were at the Kuza Awards, which is like the Emmy's here, and we won for our local children's content and and won for setting the quality standard for copyright compliance. Not many awards were handed out and we were one of only two companies that got two. We are getting recognition in Kenya and are interested in geographic expansion.

We told our investors in our business plan that we would be on the air six months after getting funding. We were able to get on the air in six and a half months, growing from two people to fourteen. All the business planning and thinking we did before we received funding was what allowed us to get on the air quickly. Fortuitously, we ended up going live throughout Kenya, the first free channel, three weeks after the country shut down for COVID. All the kids were sent home from school, and a curfew was implemented. Many parents were suddenly working from home, and in Kenya you have one-screen families. It's not like you have two kids who each have their own iPad and laptop. There's one TV. Our first measure of viewership came out four months after we went on the air and we were already the number two channel in Kenya. I attribute that to COVID and the gap in the market. At the Kuza Awards in Nairobi, I had people saying, "I'm a parent, and I love what you're bringing here." So that was confirmation of our thesis. The other part of our thesis was that the gap in the market existed because parents wouldn't want their kids to spend electricity watching TV, especially if it's not good for them. Had we gone for pure entertainment, I don't think we would have been as successful in terms of the positive feedback and viewership we currently have.

I noticed with my daughter, when she was graduating from college, how different things are today than when I was graduating. Today you're thinking, "I'm here, and I'm going to go there, and then I'll get there." When I came out of college it was, "I want to work in film" with no thought about career path. After two or three jobs, I was working as a soundman and editor for a company that did a lot of work for German television, doing a mix of news and art documentaries and working with one of my best friends from St. Stephen's, who helped me get that job. One day we decided we could do this better than the people we're working for and left to set up our own company, Seven Hills Productions. Then, three or four years later, my partner met a famous opera singer and got interested in opera. I'm not interested in opera, so we parted ways.

I found that new opportunities that often would present themselves through personal connections. You would kind of go, "Oh, that sounds interesting. I'll do that." When people ask me, "you work in television, have you done anything I might have heard of?" Although it's now quite a while ago, I produced the first season of Pee-Wee's Playhouse. That job came about through someone I met through a St Stephen's connection who thought to interview me for the job and hired me to be her boss. Then, there was another opportunity to work on a documentary for a series on PBS on American poets; I said yes. Then a week later, the President of Nickelodeon asked me if I would work for them. I had just taken this other job, so this incredible opportunity to work at Nickelodeon didn't happen. But then, five years later, that same person, who is now one of the investors in Akili, recommended me for a job in San Francisco to be CEO of Living Books, the first company doing interactive CD ROMs for kids, which was a fantastic job. So, I didn't end up at Nickelodeon, ended up moving out of TV, an early immigrant into digital.

Over the years there will be forks in road and opportunities that come up. You need to evaluate, "Is this right for me? What can I learn?" And you pick the one that seems the most interesting, you do that for a while, and then that company gets sold, and you're looking for the next job, and you land somewhere else. I'm comfortable with uncertainty and risk and I've found that adaptability is a great asset. Akili is the first time I've ever run a TV network. I think it's good to take a job where you know maybe 80% of what the job entails, but it's always good to have that 20% where you're stretching.

Follow your passions, particularly when you're starting out, when you have a low-cost structure, you don't have kids and you don't have a mortgage. That's the best time to follow your passions. And if you don't know what those are, then keep exploring, keep learning, and keep accumulating experiences until you discover your passions. If you can find something that you're excited about, it doesn’t feel like work. Sure, some days you're doing “boring” stuff, and some days it's much more interesting, but it doesn't really feel like work because it's something you want to do. I found my passion early in life, but it's never too late to do something new. The idea that someone might go down one path for five years and then realize, "I thought I was passionate about this, but I'm not," switching is perfectly fine and reasonable to do. Since most of the St. Stephen's graduates are going off to university or college, I'd say “If I had to do it all over again, I wish I'd taken more advantage of it when I was in college”. I would have liked to do two years of college and then taken a year off, worked, and then gone back and realized, "OMG, college is amazing!" You can devote yourself to exploring and learning something. That's extraordinary. It becomes a little bit harder to have that total freedom once you're in the workplace, so make the most of it!